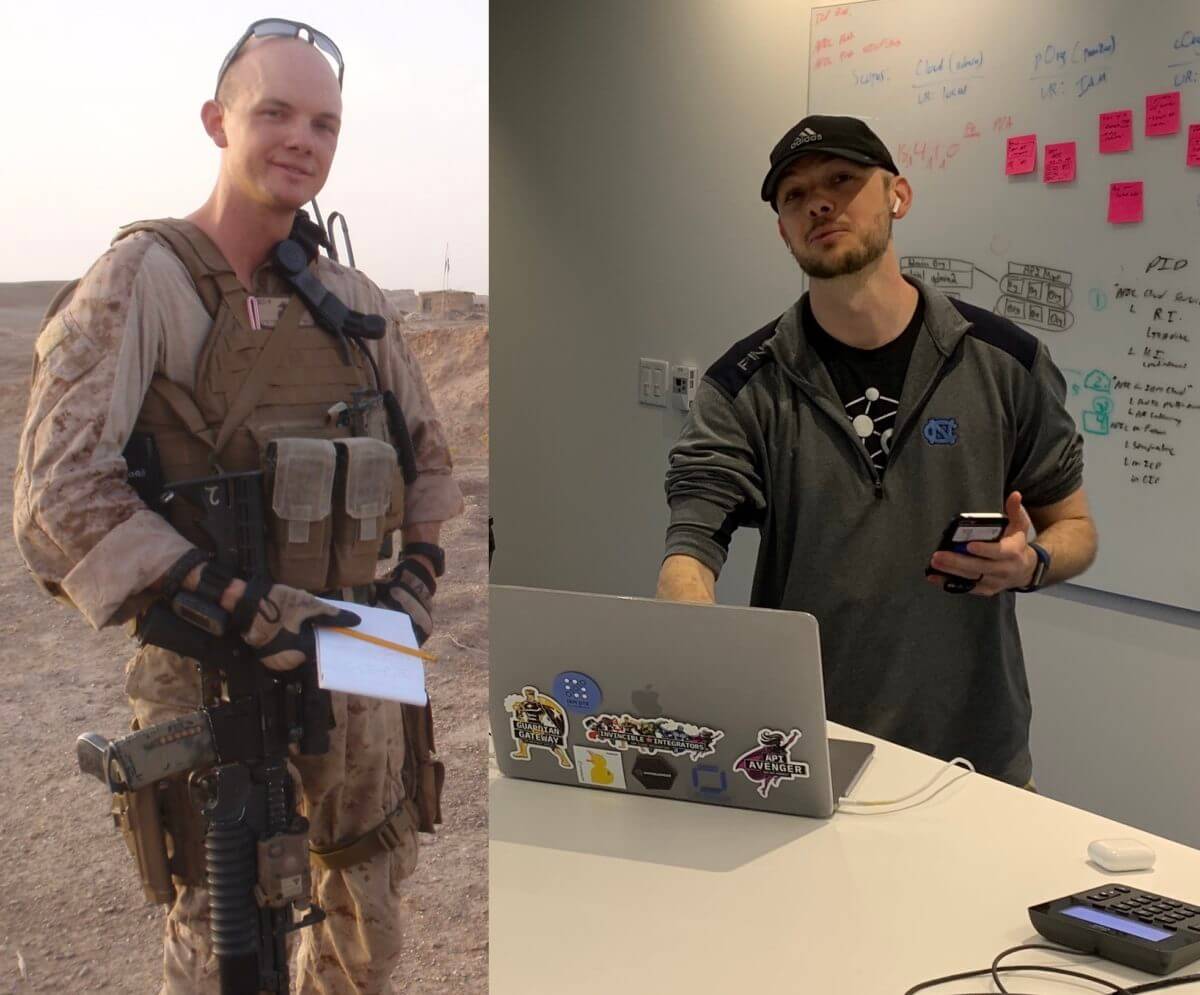

What can this guy … possibly teach this guy about creative product work?

I am a product manager at IBM; in a past life, I led Intelligence and Operations in the US Marine Corps. During my military experience, I learned some valuable lessons that have helped frame my work in product. I’d like to share some of those key learnings so other PMs can apply them to their own careers.

There is a fairly common misconception that those with military experience are extremely strict or require excessive structure. People tend to think of veterans as “order takers” who aren’t comfortable, confident, or experienced with applying creative thinking and collaborative approaches to changing conditions and/or unanticipated problems.

It’s one of those strange misperceptions that’s understandable on its face and yet very far from the truth. Hopefully, by the end of this article, we’ll have explored how similar product and military leadership are, how they both innovate through massive conceptual change, and why veterans often have a special advantage in the PM field.

An Officer and a Product Manager

If you had met me in my days as a young officer candidate, striving to complete the Marine Corps’ Officer Candidate School in Quantico, Virginia as diligently and obediently as possible, you might have found the “overly structured” stereotype very apt.

Four years later, you might instead have seen military creativity and collaboration in action. I was in Dehmazang, Afghanistan, sitting with a mixed team of soldiers, sailors and Marines, both officer and enlisted, in the plywood shack we’d built with our Afghan colleagues. We were bouncing ideas back and forth on how best to train our Afghan mentees, bring security to local villagers, and govern our own operations.

With no external set of rules to rely on, we had to create our own. We collaborated to set our own goals and build our own communication framework, mixing information and advice we had brought from training and previous experience. The structure we created freed us from indecision and endless analysis, consideration, pondering, and debate in moments of crisis. It even allowed members of our team to perform heroically when needed.

So, why am I telling you all this? Because military professionals and product managers actually have a lot in common and plenty to learn from one another. We’re all in the business of meeting human needs by creating an experience, product, or service; then we test whether our solutions meet those needs as well as, or better than, other options.

A History Lesson

In the past, the most capable and successful military units focused on the enemy. Leaders ensured that units didn’t “turn inward” or get by doing what was easiest for the unit to do. That was how you lost battles to the enemy.

Hey, did you notice we could have re-written the previous paragraph to describe companies?

In the past, the most capable and successful companies focused on the competition. Marketing and product leaders ensured that the company didn’t “turn inward” or get by doing what was easiest for the organization to do. That was how you lost market share to your competitors.

This “beat the competition/adversary” mentality may have worked at some point in time. But that is no longer the case.

Both military and product leaders must innovate around new technologies, even though they may spend their early training learning from those who went before them. For example, I spent many hours training in the dense undergrowth of Quantico, an analog for the jungles of Vietnam.

It’s often said that armies are always preparing for the last war. Likewise, companies often optimize for the era in which they first became successful. In business school, we poured over how companies like General Electric had organized and deployed resources. These previous generations provide newcomers with frameworks, a structure with which to understand the world. But what happens when the world has changed?

Let’s take aviation as an example. Suddenly, there was literally a new dimension to warfare. What did this new paradigm impact? Scouting and intelligence, armor, artillery, infantry, logistics, naval and special operations … basically everything.

What about the effect of aviation on business? Communications, transportation, negotiation, sales, finance … basically everything. So, massive changes forced both sets of leaders to adapt to new conditions. But what tectonic shift could have occurred to drive military and product leaders to new innovation in the last decade?

A Focus on People

In the military, this is called “counterinsurgency.” In the product world, it’s known as”user focus/customer obsession/consumer delight” (or some mashup of these terms). What drove this change in paradigm was the fundamental realization of a new, true goal: To meet the needs of the population better than the adversary and to have the people’s confidence, trust, and expectation that our team would always be best able to meet their needs.

Understanding this concept led us to radically reform our efforts. (Hey, was I talking about the military or product teams there?) And it’s not enough to observe the surface behavior or requests of our users. The very famous quote from Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs illustrates this:

“Some people say, ‘Give customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, “A faster horse!”’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

A lot has been written and spoken on the topic of how to dig deeper into real user needs (including this great Product Love Podcast episode featuring Eric Boduch and Cindy Alvarez). I experienced moments, both in the military and as a PM, when this lesson was truly critical.

Learning to understand people’s need even more deeply than they do themselves can be as crucial in Afghan villages (I wrote another article specifically on this) as it is in the modern software field. I’ll take Slack adoption as a software-related example. At IBM, employees moved from the previously mandated in-house instant messenger to Slack. Why? Simply put, it met their communication and collaboration needs far better. Thus, we see the recent paradigm shift to the individual and his or her needs affecting both military and product leaders.

Three Key Lessons

So, there are some very interesting similarities and likely lots of parallel and transferable skills and both must adapt, but what are military leaders uniquely qualified to offer to product leaders as insights? I’ll contend that there are three key lessons we can offer (and I plan to write an article on each one):

- Leadership

- Knowing and responding to your adversary

- The lesson of this introductory article.

So what is the lesson of this first article? Remember the myth we started the article with: that military members are too strict and always need too much structure? Well, there’s a kernel of truth there. We do have an appreciation for structure, rules, and playbooks. Because we’ve been trained in both structure and chaos, we’ve observed when and where to apply more or less structure and what types of frameworks or sets of rules best fit the situation. As we’ve innovated through one of the largest paradigm shifts in recent history, we’ve become very experienced in balancing structure, creativity, and culture to accomplish our missions in service of people.

Want to start a great conversation with a military veteran that might yield further insights on how to manage products? Ask them which rules they’ve found most helpful to apply to different circumstances, and which have been most useful to break!